Research Statement

Fish are a the last wild caught protein source on the planet. Fisheries both marine and freshwater support over 3 billion people around the earth nutritionally and economically. Unfortunately, aquatic ecosystems around the world are threatened. In this era of rapid climatic and environmental change understanding how aquatic organisms respond and predicting species outcomes will be essential for global food security and economic prosperity as well as human and ecosystem health. Managing our aquatic ecosystems requires understanding fish across scales. My work uses physiology to understand fish at their level. The challenge of integrating organism physiology to predict ecosystem response is the inspiration driving my research. At the core, I seek answers to these questions:

- How do fish respond to environmental change?

- How might changes to the landscape improve the capacity for fish, populations or species to survive?

- What are the strategies and principles for building ecosystem understanding from the bottom up?

I have approached these questions and others through several ongoing research projects. I am always open to new collaborations and novel applications of fish physiology.

Project Summaries

Interpopulation Variation among Chinook Salmon

Research on other salmonid species (Eliason et. al 2011, Stitt et al. 2014) demonstrates that individual populations of salmon can exhibit unique physiological traits which reflect the environmental conditions of their natal rivers. Chinook salmon Onchorhynchus tshawytscha exists as a large, complex, metapopulation complex along the Western Coast of North America. This project seeks to explore how different populations of Chinook salmon from across the West Coast of the United States differ in regards to their thermal physiology and metabolism. We hypothesize that populations from further north (e.g. Washington) may exhibit reduced physiological performance at warm temperatures than southern populations in California. Although we are keeping an eye on alternative drivers of population variation (e.g. local environmental conditions, migration route, anthropogenic effects etc.) We are testing our hypotheses by measuring several traits of thermal physiological performance; temperature-dependent growth, critical thermal maximum and aerobic scope. I am also quantifying the capacity for each population to acclimate to changes in water temperature by rearing each populations across a shared temperature regime. This project was funded in part by the EPA and USFWS with the intention of informing management criteria and conservation goals for protecting Chinook salmon populations. Results form this work have just been published, check them out here.

The role of food availability on thermal tolerance of juvenile Chinook Salmon

Complementing work studying trophic interactions, I am investigating how food availability influences the capacity of juvenile Chinook salmon to tolerate heat stress. Building upon a hypothesis proposed by Lusardi et al. 2020, I and fellow graduate student Cassidy Cooper are conducting a paired laboratory and field experiment.

In the lab, we reared juvenile salmon at three temperatures (11, 16 and 20°C) and exposed them to three rations of food availability (low, medium and optimal) so as to force an energetic challenge upon rearing salmon. We hypothesized that when facing an energetic restriction, juvenile salmon will be forced to make tradeoffs and may sacrifice thermal tolerance and capacity more than well-fed fish. Upon fish reared under these different conditions Cassidy and I measured growth rate, critical thermal maximum, burst performance, upper incipient lethal limits and metabolism. The results of this study are currently being analyzed.

This past winter (2022), Cassidy and I conducted a complementing field experiment which caged juvenile salmon in field locations which experience different thermal regimes and food availabilities. In doing so they hope to test whether laboratory derived results will match those observed in the field, or whether new, interesting dynamics of field rearing appear.

Temperature X. Trophic Interactions

Lots of research focuses on the impacts of temperature (or other stressors) on a single species. However in the wild, organisms never contend with just one stressor, and often the impact of multiple stressors is counter-intuitive. In my laboratory trials on Chinook salmon, we observed successful growth at 20°C and impressive swim performances at temperatures in excess of 22°C. In the wild, juvenile Chinook salmon do really poorly, with reduced outmigration and population recruitment at temperatures exceeding 20°C. This begs the question, what ecological factors are reducing the thermal physiological capacity of juvenile Chinook salmon?

I am collaborating on this project with Alex McInturf a fellow Ph.D. student. Together we are testing how trophic interactions between Chinook salmon and common Central Valley predators (e.g. largemouth bass, striped bass etc.) are mediated by temperature, and whether any lab-based physiological traits are capable of predicting the outcomes of predatory interactions. This project combines physiology, ecology, behavior and biotelemetry to reach across biological scales. Results from this project were just published, check them out here.

Climate Change Impacts on Antarctic Fish

In 2018 I was invited to join Dr. Anne Todgham’s B-207-M Antarctic Research team to conduct physiological work on juvenile fish at McMurdo Station. This suite of experiments sought to explore the effect combined effects increasing CO_2 emissions. CO_2 has two primary effects upon marine ecosystems. The first is increasing temperatures and the second is increasing acidification. In the Antarctic, ocean conditions have remained unchanged for millions of years, so even slight changes in ocean conditions may have pronounced effects upon Antarctic organisms which have evolved to very specific and specialized conditions.

These projects worked with Antarctic rock cod (*Trematomus bernacchii*), bald notothens (*Pagothenia borchgrevinki*), and the sharp-spined notothen (*Trematomus pennellii*). We conducted comparisons between species, a first look at the physiological variation that may exist among juveniles of Antarctic species. We focused upon *T. bernacchii* (aka. Bernies) to understand how the combined stressors of increasing temperature and increasing ocean acidity influence their metabolism, behavior and tissue physiology. Finally, we constructed a temperature preference apparatus to assess the temperature preference of the different Antarctic species.

Development of Experimental Equipment

Something I have found a passion for is the design and implementation of novel research devices. Studying wild animals in the lab requires unique and unusual tools in order to tease out the physiological or performance metrics needed. Below are two examples of physiological research devices I have designed or built.

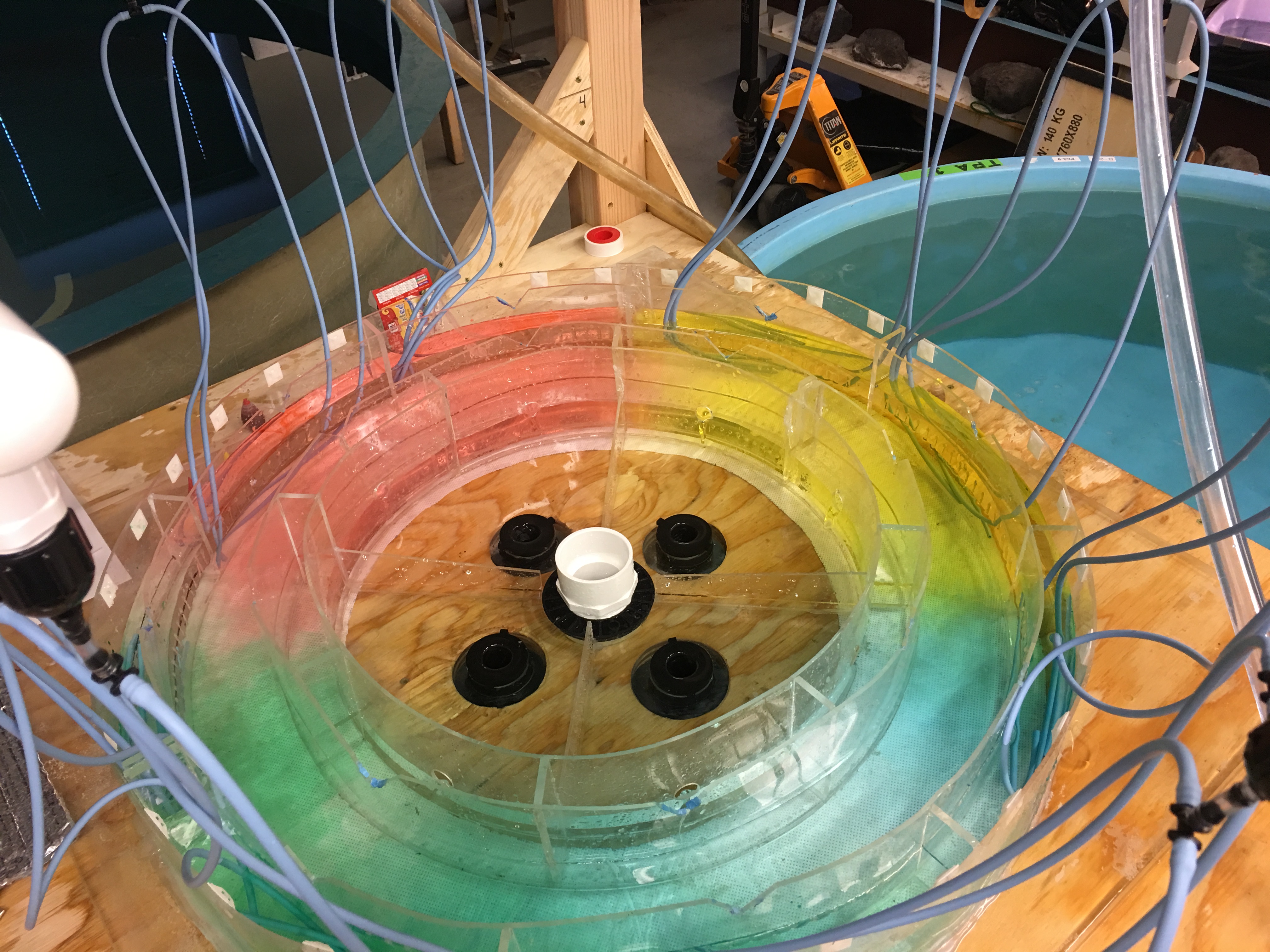

Temperature Preference Apparatus (TPA)

The TPA was originally designed in Dr. Joe Cech’s lab to quantify the thermal preference of a fish. Past methods of quantifying thermal preference often confound a thermal gradient with depth of water or tank architecture (e.g. corners and edges). This design presents a fish with a annular chamber with temperature being the only variable. An overhead camera monitors the fish’s location. In the above photograph, food dye was used to test the stability of the water gradient. In practice water of different temperatures would flow into the ring. Check out Cocherell et al. (2014) to see how the Fangue lab has used the TPA in the past.

In Antarctica we deployed two identical rings to assess how Antarctic fish, which exist in a very stable thermal environment, would respond to the opportunity to select a temperature. Deployment in Antarctica posed unique challenges that inspired a recirculating design which conserves water and energy usage and will hopefully allow for using the TPAs in remote field locations to study wild fish in their natural environment. Check out a summary here.

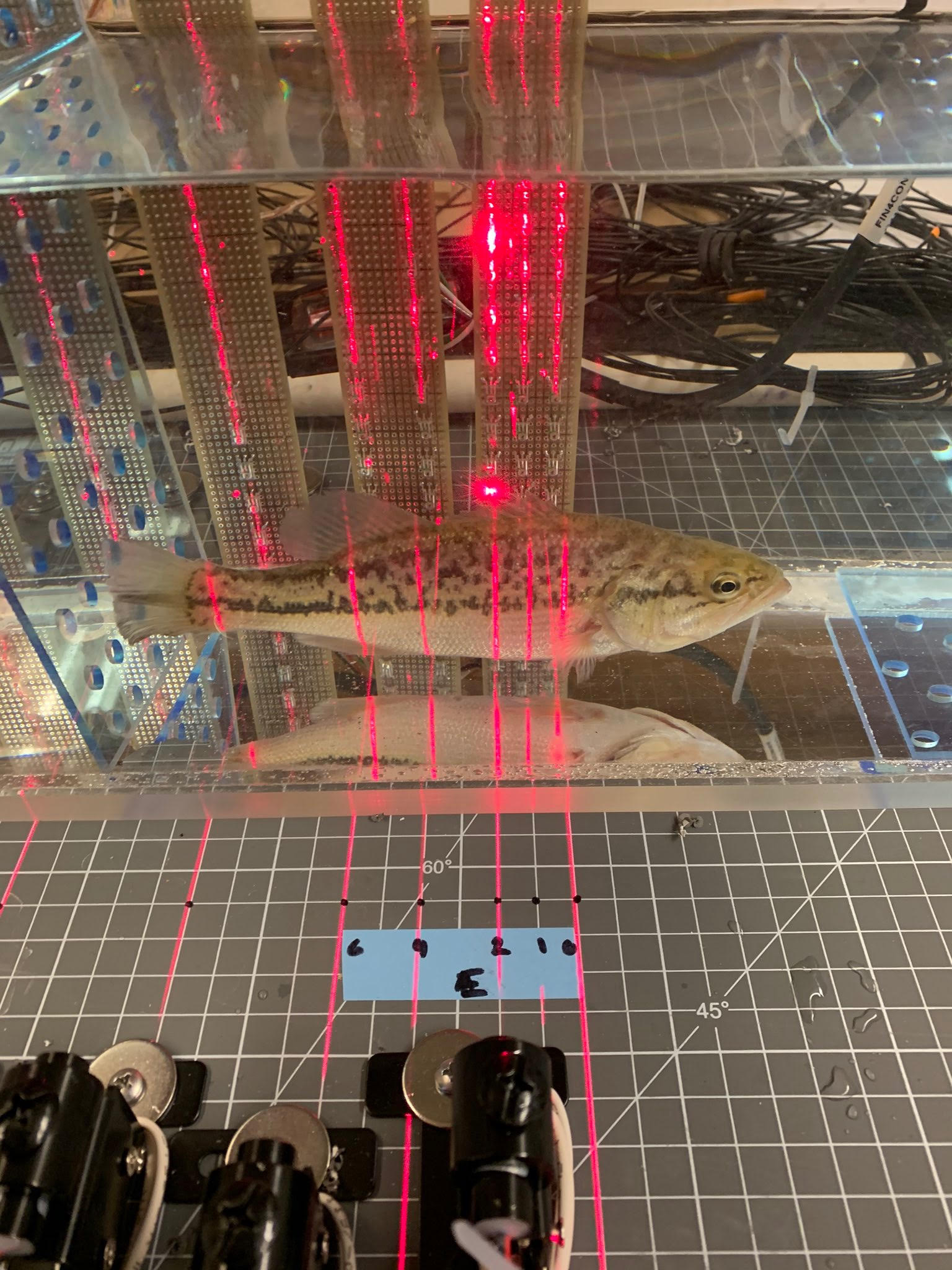

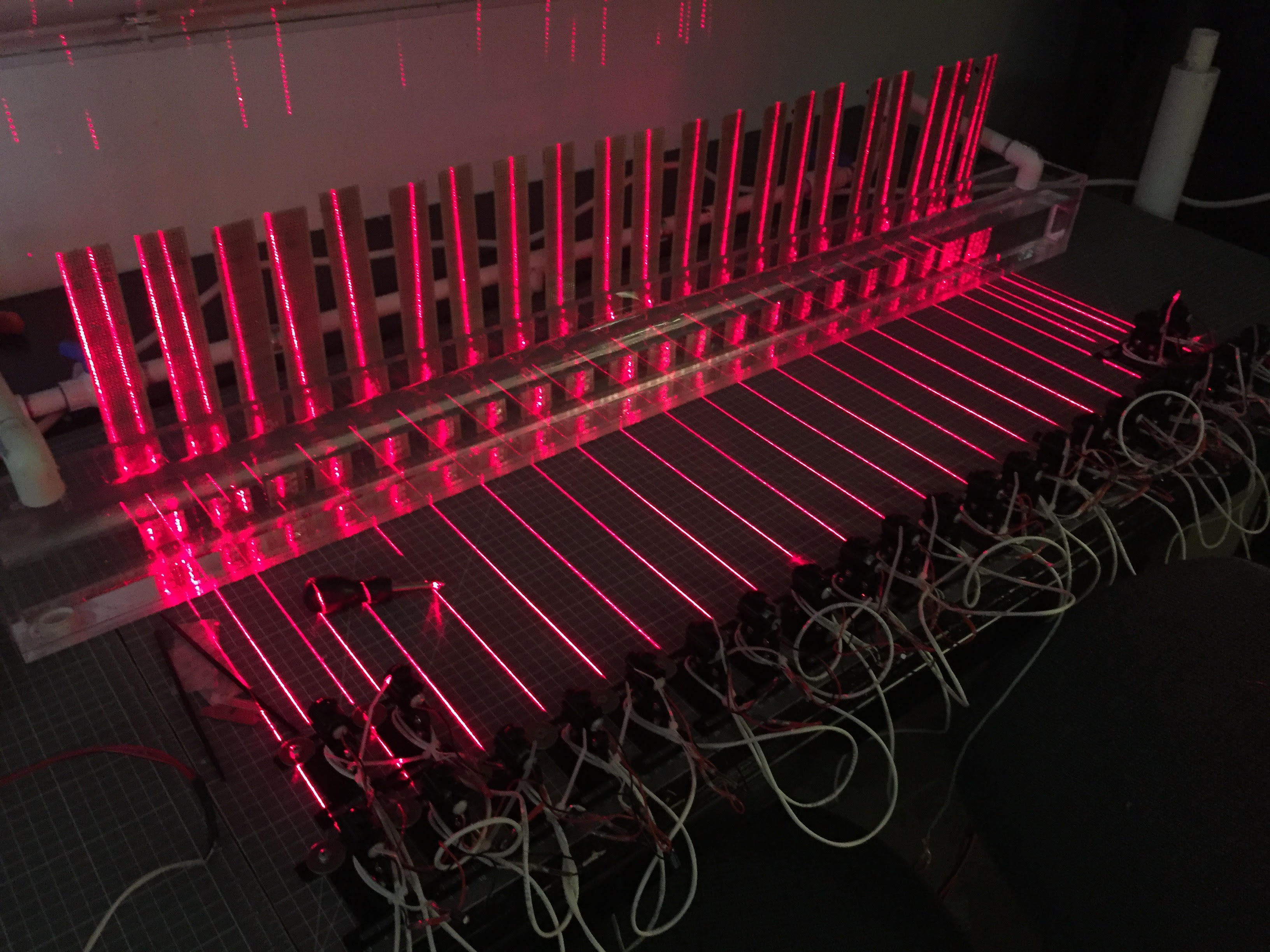

Burst Swim Performance Tunnel

Measuring aerobic capacity is relatively straight forward using oxygen consumption as a proxy. However, anaerobic metabolism, which doesn’t consume oxygen is a trickier thing to measure. In pursuit of that goal I improved upon a design for a burst swim performance tunnel as described by Nelson et al. (2002). The new design features 24 laser gates and data is collected by a simple Raspberry Pi. The new design also allows for fish to burst swim from either end, allowing for rapid, repeated trials meant to induce anaerobic fatigue. The array of lasers and associated detectors are completely customizable to accommodate different fish morphologies and behaviors. More about this project can be found hereA huge shout out to Scott Burman and Alex McInturf for their help in the design and construction of the Burst Tunnels.

The burst tunnel is currently being used to assess the temperature-dependent burst capacity of juvenile Chinook salmon, green and white sturgeon and largemouth bass. Our hope is to add delta smelt, striped bass and rainbow trout to the list of tested species.